Ahom Dynasty

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Ahom Dynasty (1228–1826) ruled the Ahom Kingdom in present-day Assam for nearly 600 years. The dynasty was established by Sukaphaa, a Shan prince of Mong Mao who came to Assam after crossing the Patkai mountains. The rule of this dynasty ended with the Burmese invasion of Assam and the subsequent annexation by the British East India Company following the Treaty of Yandabo in 1826.

In medieval chronicles, the kings of this dynasty were called Asam Raja, whereas the subjects of the kingdom called them Chaopha (Chao-god, Pha-heaven), or as Swargadeo (the equivalent in Assamese) from the 16th century.

Contents |

Swargadeo

The Ahom kings (Ahom language: Chao-Pha, Assamese language: Swargadeo), were descendants of the first king Sukaphaa (1228–1268) who came to Assam from Mong Mao in 1228.[1] Succession was by agnatic primogeniture. Nevertheless, following Rudra Singha's deathbed injunction four of his five sons became the king one after the other. The position of Swargadeo was reserved for the descendants of Sukaphaa and they were not eligible for ministerial positions—a division of power that was followed till the end of the dynasty and the kingdom. When the nobles asked Atan Burhagohain to became the king, the Tai priests rejected the idea and he desisted from ascending the throne.

The king could be appointed only with the concurrence of the patra matris (council of ministers—Burhagohain, Borgohain, Borpatrogohain, Borbarua and Borphukan). During three periods in the 14th century, the kingdom had no kings when acceptable candidates were not found. The ministers could remove unacceptable kings, and it used to involve executing the erstwhile king. In the 17th century a power struggle and the increasing number of claimants to the throne resulted in kings being deposed in quick succession, all of whom were executed after the new king was instated. To prevent this bloody end, a new rule was introduced during the reign of Sulikphaa Lora Roja—claimants to the throne had to be physically unblemished—which meant that threats to the throne could be removed by merely slitting the ear of an ambitious prince. Rudra Singha, suspecting his brother Lechai's intention, mutilated and banished him. The problem of succession remained, and on his deathbed he instructed that all his sons were to become kings. One of his sons, Mohanmala, was superseded, who went on to lead a rebel group during the Moamoria rebellion. The later kings and officers exploited the unblemished rule, leading to weak kings being instated. Kamaleswar Singha (son of Kadam Dighala) and Purandar Singha (son of Brajanath and one of the last kings of this dynasty) came into office because their fathers were mutilated.

The Ahom kings were given divine origin. According to Ahom tradition, Sukaphaa was a descendant of Khunlung, who had come down from the heavens and ruled Mong-Ri-Mong-Ram. During the reign of Suhungmung (1497–1539) which saw the composition of the first Assamese Buranji and increased Hindu influence, the Ahom kings were traced to the union of Indra (identified with Khunlung) and Syama (a low-caste woman), and were declared Indravamsa kshatriyas, a lineage created for the Ahoms.[2] Suhungmung adopted the title Swarganarayan, and the later kings were called Swargadeos (Lord of the heavens).

Coronation

The Swargadeo's coronation was called singari-ghar-utha, a ceremony that was performed first by Sudangphaa Bamuni Konwar (1397–1407). This was the occasion when the first coins in the new king's name were minted. Kamaleshwar Singha (1795–1811) and Chandrakanta Singha's (1811–1818) coronations were not performed on the instructions of Purnananda Burhagohain. Kings who died in office were buried in vaults called Moidam, at Charaideo. Some of the earlier Moidams were looted by Mir Jumla in the 17th century, and are lost. Some later kings, especially with Siba Singha (1714–1744), who were cremated had their ashes buried.

On ascent, the king would generally assume an Ahom name decided by the Ahom priests. The name generally ended in Pha (Tai: Lord), e.g. Susenghphaa. Later kings also assumed a Hindu name that ended in Singha (Assamese: Lion): Susengphaa assumed the name Pratap Singha. Buranjis occasionally would refer to a past king by a more informal and colorful name that focused on a specific aspect of the king. Pratap Singha was also known as Burha Roja (Assamese: Old King) because when Pratap Singha became the king, he was quite advanced in age.

Royal offices

Subinphaa (1281–1293), the third Ahom king, delineated the Satghariya Ahom, the Ahom aristocracy of the Seven Houses. Of this, the first lineage was that of the king. The next two were the lineages of the Burhagohain and the Borgohain. The last four were priestly lineages. Sukhramphaa (1332–1364) established the position of Charing Raja which came to be reserved for the heir apparent. The first Charing Raja was Sukhramphaa's half-brother, Chao Pulai, the son of the Kamata princess Rajani, but who did not ultimately become the Swargadeo. Suhungmung Dihingia Raja (1497–1539) settled the descendants of past kings in different regions that gave rise to seven royal houses—Saringiya, Tipamiya, Dihingiya, Samuguriya, Tungkhungiya, Parvatiya and Namrupiya—and periods of Ahom rule came to be known after these families. The rule of the last such house, Tungkhungiya, was established by Gadadhar Singha (1681–1696) and his descendants ruled till the end of the Ahom kingdom.

Queens

Ahom queens (Kunworis) played important roles in the matter of state. They were officially designated in a gradation of positions, called the Bor Kuwori (Chief Queen), Parvatia Kuwori, Raidangia Kuwori, Tamuli Kuwori, etc. who were generally daughters of Ahom noblemen and high officials. Lesser wives of the Swargadeo were called chamua kunworis. Some of the queens were given separate estates that were looked after by state officials (Phukans or Baruas) (Gogoi). During the reign of Siba Singha (1714–1744), the king gave his royal umbrella and royal insignia to his queens—Phuleshwari Kunwori, Ambika Kunwori and Anadari Kunwori in succession—to rule the kingdom. They were called Bor-Rojaa.

One way in which the importance of the queens can be seen is that many of them are named on coins; typically the king's name would be on the obverse of the coin and the queen's on the reverse.

Court influences

Sukaphaa's ruling deity was Chomdeo a non-Hindu, non-Buddhist god, and he was accompanied by classes of priests called Deodhai, Bailung etc. But the Ahom kings let themselves be influenced by the religion and customs of those they ruled over. The first Hindu influence was cast during the reign of Sudaangphaa Bamuni Konwar (1397–1407), who had grown up in a Brahmin household. Suhungmung Dihingia Rojaa (1497–1539) was the first Ahom king to expand the kingdom and the polity, allow Assamese influence in his court and accept a non-Ahom title—Swarganarayan. Assamese coexisted with Tai till the reign of Pratap Singha (1603–1641), during whose rule Assamese became dominant. Sutamla (1648–1663) was the first Ahom king to be initiated into the Mahapuruxiya Dharma. Mahapuruxiya pontiffs belonging to different sects began playing a greater role in state politics. After the chaos of the late 17th century, Gadadhar Singha (1681–1696), the first Tungkhungiya king began his rule with a deep distrust of these religious groups. His son and successor Rudra Singha (1696–1714) searched for an alternative state religion, and his son and successor Siba Singha (1714–1744) formally adopted Saktism, the nemesis of the Mahapuruxiya sects. The persecution of the Mahapuruxiya Sattras under the Tunkhungiya rulers following Siba Singha was a crucial factor leading to the Moamoria rebellion that greatly depleted the Ahom kingdom.

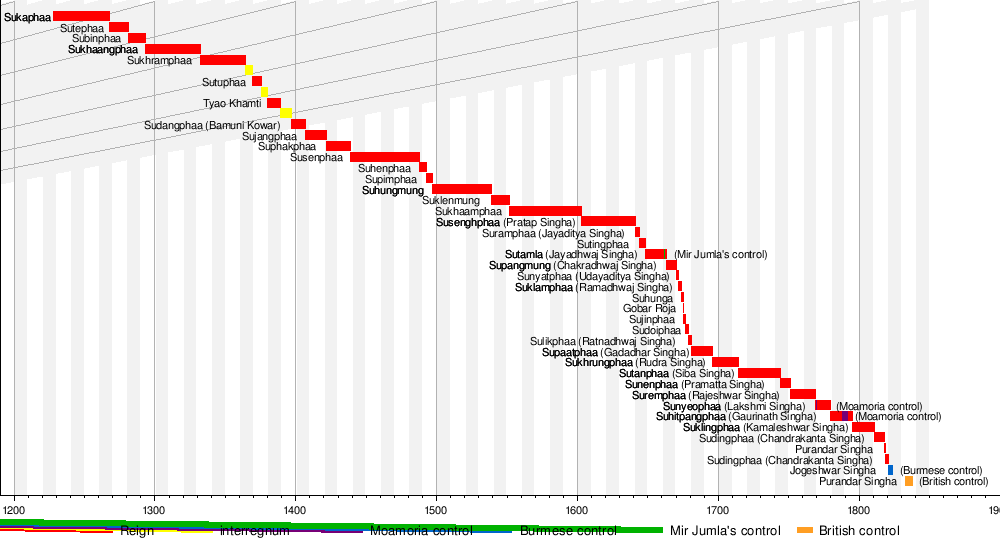

Timeline

Swargadeo dynastic lineage

In the nearly 600-years 39-Swargadeo dynastic history, there are three progenitor kings (all subsequent kings are descendants of these kings). They are Sukaphaa, who established he kingdom; Suhungmung, who made the greatest territorial and political expansion of the kingdom; and Supaatphaa, who established the House of Tungkhugia kings that reigned the kingdom during its political and cultural zenith, as well as the period of decay and end.

The dynastic history and dates that are accepted today are the result of a re-examination of Ahom and other documents by a team of Nora astronomers and experts who were commissioned to do so by Gaurinath Singha (1780–1795).[4]

| Years | Reign | Ahom name | Other names | succession | End of reign | Capital |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1228–1268 | 40y | Sukaphaa | natural death | Charaideo | ||

| 1268–1281 | 13y | Sutephaa | son of Sukaphaa | natural death | Charaideo | |

| 1281–1293 | 8y | Subinphaa | son of Sutephaa | natural death | Charaideo | |

| 1293–1332 | 39y | Sukhaangphaa | son of Subinphaa | natural death | Charaideo | |

| 1332–1364 | 32y | Sukhrampha | son of Sukhaangphaa | natural death | Charaideo | |

| 1364–1369 | 5y | Interregnum | ||||

| 1369–1376 | 7y | Sutuphaa | brother of Sukhramphaa | assassinated[5] | Charaideo | |

| 1376–1380 | 4y | Interregnum | ||||

| 1380–1389 | 9y | Tyao Khaamti | son of Sukhaangphaa | assassinated[6] | Charaideo | |

| 1389–1397 | 8y | Interregnum | ||||

| 1397–1407 | 10y | Sudangphaa | Baamuni Kunwar | son of Tyao Khaamti[7] | natural death | Charagua |

| 1407–1422 | 15y | Sujangphaa | son of Sudangphaa | natural death | ||

| 1422–1439 | 17y | Suphakphaa | son of Sujangpha | natural death | ||

| 1439–1488 | 49y | Susenphaa | son of Suphakphaa | natural death | ||

| 1488–1493 | 5y | Suhenphaa | son of Susenphaa | assassinated[8] | ||

| 1493–1497 | 4y | Supimphaa | son of Suhenphaa | natural death | ||

| 1497–1539 | 42y | Suhungmung | Swarganarayan, Dihingiaa Rojaa I |

son of Supimphaa | assassinated[9] | Bakata |

| 1539–1552 | 13y | Suklenmung | Garhgayaan Rojaa | son of Suhungmung | natural death | Garhgaon |

| 1552–1603 | 51y | Sukhaamphaa | Khuraa Rojaa | son of Suklenmung | natural death | Garhgaon |

| 1603–1641 | 38y | Susenghphaa | Prataap Singha, Burhaa Rojaa, Buddhiswarganarayan |

son of Sukhaamphaa | natural death | Garhgaon |

| 1641–1644 | 3y | Suramphaa | Jayaditya Singha, Bhogaa Rojaa |

son of Susenghphaa | deposed[10] | Garhgaon |

| 1644–1648 | 4y | Sutingphaa | Noriyaa Rojaa | brother of Suramphaa | deposed[11] | Garhgaon |

| 1648–1663 | 15y | Sutamla | Jayadhwaj Singha, Bhoganiyaa Rojaa |

son of Sutingphaa | natural death | Garhgaon/Bakata |

| 1663–1670 | 7y | Supangmung | Chakradhwaj Singha | cousin of Sutamla[12] | natural death | Bakata/Garhgaon |

| 1670–1672 | 2y | Sunyatphaa | Udayaaditya Singha | brother of Supangmung | deposed[13] | |

| 1672–1674 | 2y | Suklamphaa | Ramadhwaj Singha | brother of Sunyatphaa | poisoned[14] | |

| 1674–1675 | 21d | Suhunga | Samaguria Rojaa | Samaguria descendant of Suhungmung | deposed[15] | |

| 1675-1675 | 24d | Gobar Rojaa | great-grandson of Suhungmung[16] | deposed[17] | ||

| 1675–1677 | 2y | Sujinphaa | Arjun Konwar, Dihingia Rojaa II |

grandson of Pratap Singha, son of Namrupian Gohain | deposed, suicide[18] | |

| 1677–1679 | 2y | Sudoiphaa | Parvatia Rojaa | great-grandson of Suhungmung[19] | deposed, killed[20] | |

| 1679–1681 | 3y | Sulikphaa | Ratnadhwaj Singha, Loraa Rojaa |

Samaguria family | deposed, killed[21] | |

| 1681–1696 | 15y | Supaatphaa | Gadadhar Singha | son of Gobar Rojaa | natural death | Borkola |

| 1696–1714 | 18y | Sukhrungphaa | Rudra Singha | son of Supaatphaa | natural death | Rangpur |

| 1714–1744 | 30y | Sutanphaa | Siba Singha | son Sukhrungphaa | natural death | |

| 1744–1751 | 7y | Sunenphaa | Pramatta Singha | brother of Sutanphaa | natural death | |

| 1751–1769 | 18y | Suremphaa | Rajeswar Singha | brother of Sunenphaa | natural death | |

| 1769–1780 | 11y | Sunyeophaa | Lakshmi Singha | brother of Suremphaa | natural death | |

| 1780–1795 | 15y | Suhitpangphaa | Gaurinath Singha | son of Sunyeophaa | natural death | Jorhat |

| 1795–1811 | 16y | Suklingphaa | Kamaleswar Singha | great-grandson of Lechai, the brother of Rudra Singha[22] | natural death, small pox | Jorhat |

| 1811–1818 | 17y | Sudingphaa (1) | Chandrakaanta Singha | brother of Suklingphaa | deposed[23] | Jorhat |

| 1818–1819 | 1y | Purandar Singha (1) | descendant of Suremphaa[23] | deposed[24] | Jorhat | |

| 1819–1821 | 2y | Sudingphaa (2) | Chandrakaanta Singha | fled the capital[25] | ||

| 1821–1822 | 1y | Jogeshwar Singha | brother of Hemo Aideo, puppet of Burmese ruler[26] | removed[27] | ||

| 1833–1838 | Purandar Singha (2)[28] |

Notes

- ^ See Sukaphaa for the origin and journey of the first Ahom king into Assam.

- ^ (Gogoi 1968:283). In standard Hindu Puranic history the two accepted families are Chandravamsi and Suryavamsi.

- ^ P.L. Gupta: Coins, 4th ed., New Delhi: National Book Trust, 1996, p. 169.

- ^ (Gogoi 1968:534–535)

- ^ Sukhramphaa was assassinated by the king of the Chutiya kingdom on a barge ride on Suffry river (Gogoi 1968:273).

- ^ Sukhangphaa and his chief queen were deposed and executed by the ministers for their autocratic rule (Gogoi 1968:274).

- ^ Sudangphaa Bamuni Konwar was born to the second queen of Tyao Khamti in a Brahmin household of Habung (Gogoi 1968:274–275).

- ^ Suhenphaa was speared to death in his palace by a Tai-Turung chief in revenge for being accused of theft (Gogoi 1968:282).

- ^ Suhungmung was assassinated by a palace staff in a plot engineered by his son, Suklenmung (Gogoi 1968:309).

- ^ Suramphaa was deposed by the ministers when he insisted on burying alive a son of each minister in the tomb of his dead step-son (Gogoi 1968:386). He was later murdered on the instructions of his nephew, the son of his brother and succeeding Swargadeo.

- ^ Sutingphaa was a sickly king (Noriaya Raja), who participated in an intrigue by his chief queen to install a prince unpopular with the ministers. He was deposed and later murdered on the instructions of his son and successor king Sutamla (Gogoi 1968:391–392).

- ^ Supangmung was grandson of Suleng (Deo Raja), the second son of Suhungmung (Gogoi 1968:448).

- ^ Udayaaditya Sinha's palace was stormed by his brother (and successor king) with a thousand-strong contingent of men led by Lasham Debera, and the king was executed the next day. Udayaaditya's religious fanaticism under the influence of a godman had made him unpopular, and the three great gohains implicitly supported this group (Gogoi 1968:479–482). This event started a very unstable nine-year period of weak kings, dominated by Debera Borbarua, Atan Burhagohain and Laluk-sola Borphukan in succession. This period ended with the accession of Gadadhar Singha.

- ^ Ramadhwaj Sinha was poisoned on the instructions of Debera Borbarua when he tried to assert his authority (Gogoi 1968:484).

- ^ The Samaguria raja was deposed by Debera Borbarua, the de facto ruler, and later executed, along with his queen and her brother (Gogoi 1968:486).

- ^ Gobar Rojaa was the son of Saranga, the son of Suten, the son of Suhungmung Dihingiya Roja.

- ^ Gobar Raja was deposed and executed by the Saraighatias (the commanders of Saraighat/Guwahati), led by Atan Burhagohain (Gogoi 1968:486–488). Their target was the defacto ruler, Debera Borbarua, who was also executed.

- ^ Sujinphaa Arjun Konwar tried to assert control by moving against the de facto ruler, Atan Burhagohain, but was routed in a skirmish. Sujinphaa was blinded and held captive when he committed suicide by striking his head against a stone (Gogoi 1968:489).

- ^ Sudoiphaa was the grandson of Suhungmung's third son, Suteng (Gogoi & 1968 490).

- ^ Sudoiphaa was deposed by Laluk-sola Borphukan, who styled himself as the Burhaphukan, and later executed. Atan Burhagohain, the powerful minister, had been executed earlier (Gogoi 1968:492–493).

- ^ Sulikphaa Lora Roja was deposed and then executed by Gadadhar Singha (Gogoi 1968:496–497).

- ^ Kamaleswar Singha was installed as the king by Purnananda Burhagohain when he was still an infant. He was the son of Kadam Dighala, the son of Ayusut, the son of Lechai, the second son of Gadadhar Singha. Kadam Dighala, who could not become the king because of physical blemishes, was an important influence during the reign (Baruah 1993:148–150).

- ^ a b Chandrakanta Singha was deposed by Ruchinath Burhagohain, mutilated and confined as a prisoner near Jorhat (Baruah 1992:221). Purandar Singha, a descendant of Suremphaa Pramatta Singha, was instated as the Swargadeo.

- ^ Purandar Singha's forces under Jaganath Dhekial Phukan defeated the forces led by the Burmese general Kee-Woomingee (Kiamingi or Alumingi Borgohain) on February 15, 1819, but due to a strategic mistake Jorhat fell into Burmese hands. Kiamingi brought back Chandrakanta Singha and installed him the king (Baruah 1992:221–222).

- ^ Chandrakanta Singha fled to Guwahati when the army of Bagyidaw king of Burma, led by Mingimaha Tilwa, approached Jorhat (Baruah 1992:223).

- ^ Jogeshwar Singha was the brother of Hemo Aideu, one of the queens of Bagyidaw. He was installed as the king by Mingimaha Tilwa (Baruah 1992:223).

- ^ Jogeshwar Singha was removed from all pretense of power and Mingimaha Tilwa was declared the "Raja of Assam" toward the end of June, 1822 (Baruah 1992:225).

- ^ Purandar Singha was set up by the East India Company as the tributary Raja of Upper Assam (Baruah 1992:244).

References

- Baruah, S. L. (1993), Last Days of Ahom Monarchy, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt Ltd, New Delhi

- Gogoi, Padmeshwar (1968), The Tai and the Tai kingdoms, Gauhati University, Guwahati

External links

- A mighty clan's website An article by Saikh Md Sabah Al-Ahmed in The Assam Tribune "Horizon", Saturday special, dated September 19, 2009

- Coins of Ahom Dynasty